ABSTRACT: Great Questions are a challenge to possibilities. A practitioner of person-centered planning who wanted to add the skills and roles of the portraitist to her repertoire would need to build relationships with people and their families and allies based on commitment to a common project that early trials of those skills and roles could serve. She would also seek connections to others interested in going deeper in their work by trying new ways of engagement and new kinds of representations of people.

Great Questions and

The Art of Portraiture

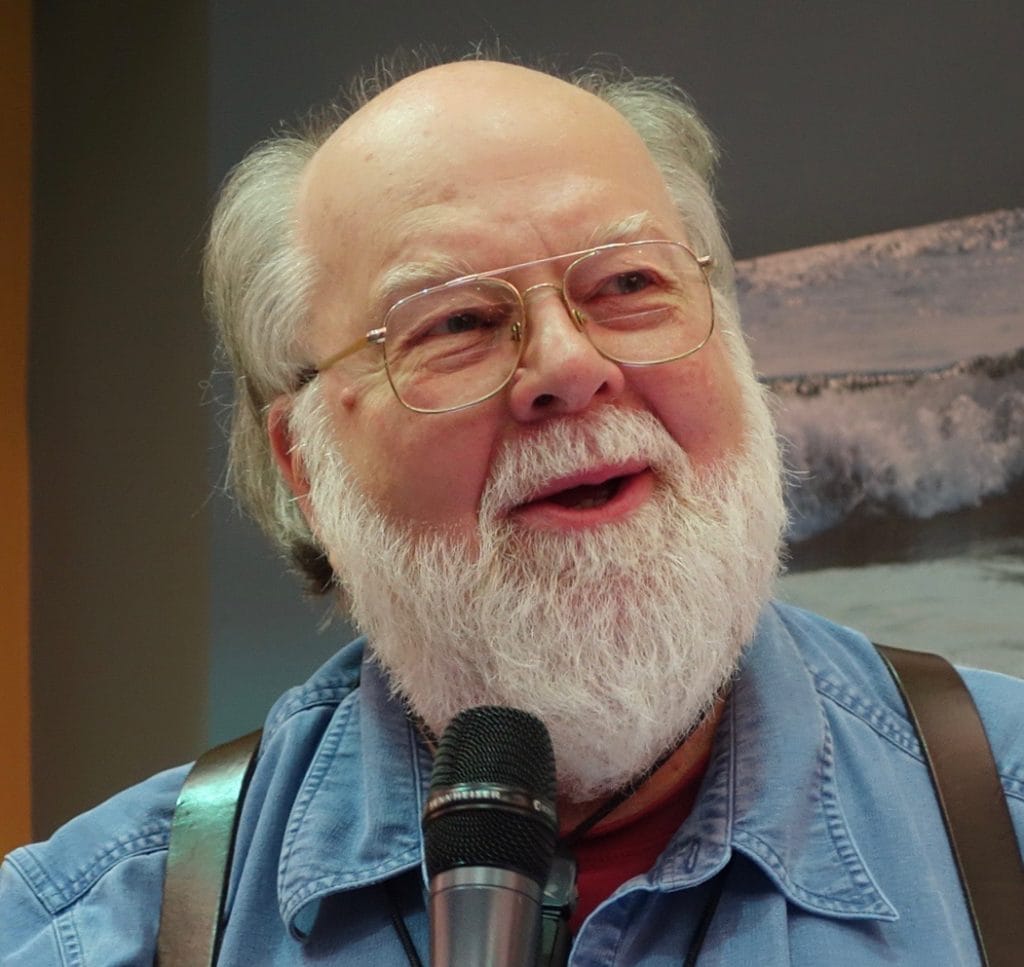

by John O’Brien

Among my friend Judith Snow’s wise sayings is her definition of a great question. “A great question refuses to be answered, and so it leads us into deeper thinking and deeper connections.” Visual play with the word shows that questions contain quests. Great questions move people into the adventure of searching together for something compellingly worthwhile. Such a search can seem too much to manage while juggling the daily requirements of survival or it can threaten too much embarrassment from the risk of seeming a poor imitator of Don Quixote. So, paradoxically, we can easily ignore great questions by refusing time for deeper thinking or withholding energy from deeper relationships. To influence us, great questions need hosts to invite their presence into busy lives and champions to remember their merit in the face of anxiety.

The hosts and champions of great questions need courage, respect, and a discipline. While great questions can be found in any field, what interests me here is the framing of great questions in the lives of people whose capacities easily get lost. Person-centered planning offers a disciplined way to search for great questions in the lives of particular people who choose it, questions that lead to deeper thinking about a person’s identity and contributions and to deeper connections to other people who matter for the person’s future. According tot he last issue of Inclusion News, Sarah, nine-year old John’s mother, has found such a question:

“Who will need to know John, and what kind of experience will they need to have with each other so that someone in our circle will offer John employment when he leaves school? What do we need to be doing together over the next ten years for this to happen?’

This is a great question because it anticipates a co-evolution of resourcefulness over the next decade. John’s identity and gifts will develop as those now close to him assist him to know and be known by a wider circle of people. The community John lives in will develop by appreciating his contributions and adapting to make room for him. Reflection on Sarah’s great question suggests a framing question for the person centered planning process. This framing question asks…

“Under what conditions can this person discover and express more of who she or he is as a known and valued contributor to our community?”

The answer to this framing question will be another question, a great question like Sarah’s if its askers work artfully. Great questions have their source in an imaginative and respectful understanding of a person’s life. The service world that surrounds many people with developmental disabilities seems less comfortable with the image of understanding people as an art than with the image of an objective science of assessment and intervention. Such an image of science appeals, in part, because it promises the sort of steady improvement in the prediction and control of people’s behavior that makes service systems more manageable. From this point of view, one gets to know a person in order to discipline need. Talk of art, imagination and great questions can sound like the trumpets of anarchy.

Those experienced in person-centered planning resist arguments for impersonal assessment as the basis of assistance for people with disabilities. A careful confidence grows from living through important changes with people who have hold of a great question about their lives in community. This confidence supports twin judgements on the sort of professionalism that serves managerial command and control in the name of objective science. Such science is dangerous insofar as its predictions trap people in professionally controlled low expectations and segregation. And, such science tells uninteresting stories by abstracting life as particular people experience it into sterile categories and roles. Objective knowledge may suffice for those medical treatments that function impersonally (though some physicians would disagree); only art will do for finding and pursuing a great question.

Confidence in the rightness of assisting people to discover and pursue great questions gives practitioners of person centered planning the courage necessary to do their work. It also exposes them to danger. Bad art is at least as common as bad science and the consequences of artistic misunderstanding can be as life-wasting or trivial as the consequences of scientific assessment too often are.

At least three kinds of relationships reduce the risk of poor understanding: 1) maintaining alliance with the people, families, and circles one plans with and making time to reflect on what aids and what hinders their journey; 2) joining with other practitioners for mutual support and coaching; and 3) linking with complementary disciplines to gain a broader perspective on the work. Links to complementary disciplines can help by suggesting different metaphors for the work, different practices, and different ethical perspectives. A brief introduction to the talented originator of a complementary discipline follows in the hope that it will persuade practitioners of person-centered planning to meet her by reading three fine books. (The books, in the order I would suggest reading them, are: Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot (1999). Respect: An exploration. Reading, MA: Perseus Books. Here she applies her approach to the investigation of a virtue that is fundamental to the work of person-centered planning. Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot and Jessica Hoffmann Davis (1997). The art and science of portraiture. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. This describes her method in relationship to visual art and to social sciences. Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot (1994). I’ve known rivers: Lives of loss and liberation. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Here are wonderful portraits of successful African-Americans told to disclose the kinds of experiences and relationships important for liberation.)

In her practice of research as portraiture, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, a sociologist at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, offers valuable resources to those who want to host the emergence of great questions in people’s lives. She thinks of herself as weaving a tapestry from the elements her subjects share with her and describes her project in words that will resonate and raise helpful questions among practitioners of person-centered planning.

Portraitists seek to record and interpret the perspectives and experience of the people they are studying, documenting their voices and their visions – their authority, knowledge and wisdom. The drawing of the portrait is placed in social and cultural context and shaped through dialogue between the portraitist and the subject… (The art and science of portraiture, p. xv.) She defines her work as a counterpoint to a social science concerned primarily with defining social problems for an elite audience.

Portraiture… seeks to illuminate the complex dimensions of goodness and is designed to capture the attention of a broad and eclectic audience. (The art and science of portraiture, p. xvi.) In Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot’s hands, the idea of portraiture is fruitful in many ways, Each of her books repays study in now techniques for exploring and presenting lives, in new ideas about the contributions of professionals and researchers, and in civic lessons drawn from people’s living wisdom. Here, I will focus on some of the contributions her work makes to my thinking about an important ethical question: what is the proper relationship between the practitioner of person-centered planning and the people she wants to serve?

For some practitioners this question has a straightforward answer. They see themselves as reflecting only what people say they want and assisting people to organize available resources to get it. The practitioner meets requirements by performing a two or three step sequence: 1) record the words people say in answer to straightforward questions about their desires and dreams; 2) facilitate the writing of an action plan for making it happen- and, sometimes, 3) gather people occasionally to check and revise the action plan.

This answer makes sense as far as it goes.. Many people do have clear and achievable ideas about what would significantly improve their lives, ideas that have gone unrealized because they have remained buried under other people’s unwillingness to listen to them and act on -what they hear. But reflection on Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot’s account of the roles she plays with the people who choose to join her in understanding what their lived knowledge and wisdom can contribute to a stronger community shows that this kind of relationship only makes a good beginning. Much more is possible when people consent to share part of their lives with someone who seeks to know them in order to serve both them and their community. As you read the following paragraph, notice the seven roles and associated activities she describes herself as playing in unfolding her subject’s lives. Then take a moment to consider the possibilities and dangers each role might hold for the practitioner of person-centered planning.

As I listen to these extraordinary women and men tell their life stories, I play many roles. I am a mirror that reflects back their pain, their fears, and their victories. I am also the inquirer who asks the sometimes difficult questions, who searches for evidence and patterns. I am, the companion on the journey, bringing my own story to the encounter, making possible an interpretive collaboration. I am the audience who listens, laughs, weeps, and applauds. I am the spider woman spinning their tales. Occasionally, I am a therapist who offers catharsis, support, and challenge, and who keeps track of emotional minefields. Most absorbing to me is the role of the human archaeologist who uncovers the layers of mask and inhibition in search of a more authentic representation of life experience. (I’ve known rivers, p. 26) Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot’s way of understanding portraiture illuminates another problem with the notion of the practitioner as simply taking accurate dictation. Portraiture works from the powerful effects of the artist on the portrait, even on a photographic portrait, and does not try to hide behind a screen of objectivity. Such a screen can be made from the fabric of positivistic science and professionalism; it can also be made from the naive idea that “I only do what the person tells me! Even mirrors lack objectivity,

… through [the arts of] documentation, interpretation, analysis, and narrative we raise the mirror, hoping -with accuracy and discipline- to capture the mystery and artistry that turn image into essence.- (The art and science of portraiture, p. xvii.) The possibility- of understanding oneself as human archeologist, spider woman, companion, inquirer, and portraitist while doing the work of person-centered planning raises difficult questions about the nature of the agreement between the practitioner and the person she assists. Is the relationship solely to benefit the person, or might it be understood more powerfully as a relationship that exists to benefit both the person and a community that acts unthinkingly against itself by excluding the person and denying the person’s contributions? Perhaps person-centered planning could serve the common good by supporting people to represent and deepen their knowledge, wisdom, vision, and authority. And perhaps the subjects of person-centered planning, like Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot’s subjects, better disclose their knowledge, wisdom, vision, and authority through engaged conversation with someone they authorize to actively inquire with them and produce a portrait of them. The imbalance of power between the practitioner and the person she assists trouble these questions in ways that raise even more difficulty than they do in the dialogue between Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot and her subjects.

A practitioner of person-centered planning who wanted to add the skills and roles of the portraitist to her repertoire would need to build relationships with people and their families and allies based on commitment to a common project that early trials of those skills and roles could serve. She would also seek connections to others interested in going deeper in their work by trying new ways of engagement and new kinds of representations of people. In this way, study of Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot’s work might be the occasion for another great question entering her life.

This essay also appeared in Realizations, Summer 2001. Copyright 2002 Inclusion Press — All rights reserved